Taruka’s Raison D'Être

A whitepaper on the founding of Taruka Technologies.

Hello. My name is Gaurav Dahal. I am a former Philosophy student at the University of Maryland. I dropped out of University with a year of credits left to get my degree to come to Nepal, the country where I was born, to build Taruka Technologies. Taruka Tech. specializes in designing and manufacturing fully electric vehicles in the context of Nepal’s developing economy.

Our Mission

I’ll begin with our mission at Taruka. As listed on our website, “our mission is to empower Nepalis to utilize the Himalayan country's hydropower resources for farming, transport and mobility by creating vehicles, tractors and other mobility equipment that aid in making daily life, food production and mobility easier.”

Let’s deconstruct this sentence. Our primary objective is to empower Nepalis. Nepal has a gross domestic product (GDP) of $33.6 Bn. Nepal’s GDP per capita is $1,155.1. It is safe to say, Nepal is poor. As of 2021, Nepal ranks 184th in a ranking of GDP per capita of countries and territories. Nepal is very poor.

Taruka’s mission is to change this fact. We aim to empower Nepalis out of the economic slump that the country is in. But we aren’t naive idealistics. If you are thinking, how do you plan to do that? Perhaps there is a reason Nepal is as poor as it is. We aren’t radical deterministics and fatalists either.

Nepal is characteristically known for its towering mountains, steep hills and flowing rivers. So much so that schoolboys and schoolgirls have a myth embedded into their brains that, “Nepal ranks second in hydropower resources”-- a fact unable to be verified despite all the statistical gymnastics. Despite Nepal's relative rankings in terms of water resources, what is true are the absolute numbers. Numbers derived from the fact that Nepal has many rivers that flow from high up to almost sea level. Nepal having a theoretical hydropower production capacity of 80,000 MW of which 40,000 MW being commercially viable is another popular statement amongst those with interest in Nepal’s energy sector.

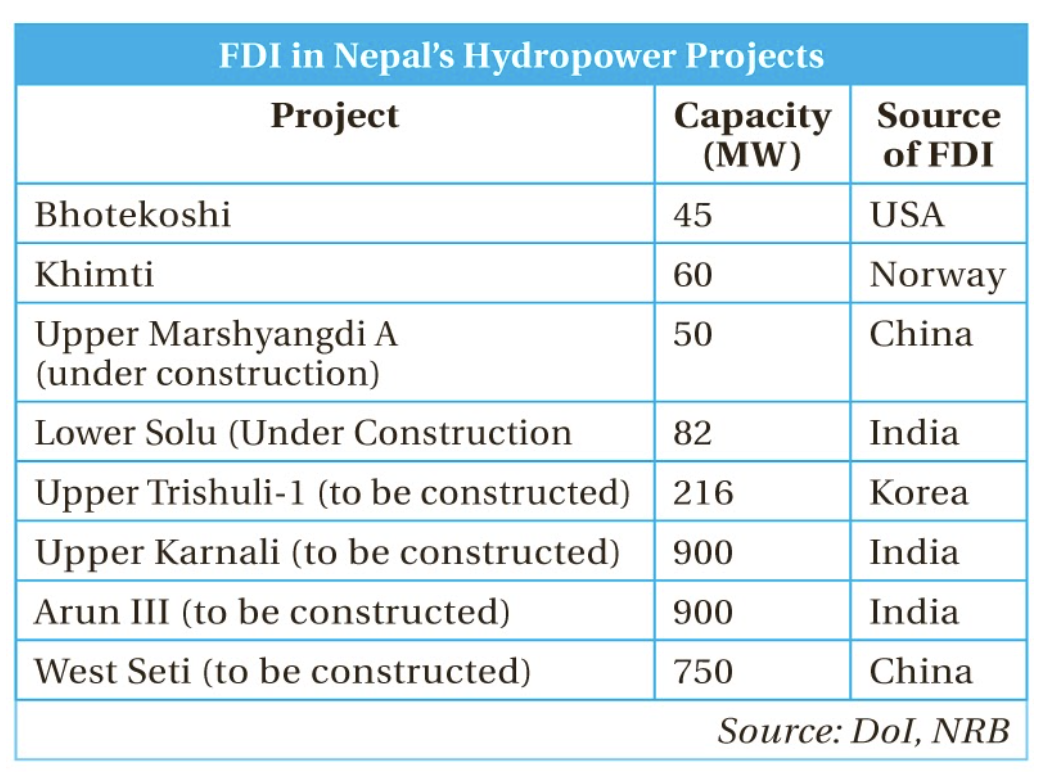

We’ve established that Nepal has hydropower potential. Bridging the gap between possiblia to reality takes a lot of investments, infrastructure and demand side development. Financing large infrastructure projects is a problem for a poor, capital-strapped nation. Physically building the infrastructure required to dam and divert large volumes of waters to runners is another challenge, where construction methods are crude and engineering knowledge limited. Finally, there is demand for consuming electricity in Nepal. However, whether this demand is for productive assets and usage is dubitable.

Generating energy for the sake of consumption only is a risky bet for the future, especially when there is a lot of foreign financing in funding the energy project, as is the case with Nepali hydropower. Energy needs to go towards productive assets-using electricity in sectors that will have a meaningful impact on GDP growth. If not, the burden of paying off bonds to foreign debt holders can encumber the country in its path to development. To drive home this point, I’ll simplify the exegesis of the argument using an example.

You plan to buy a home. There are two options on the market. Both houses cost the same but there are key differences between the two. One house, House A is most and is close to the economic center of your town. House B is far away from the economic center but is aesthetically pleasing, has more square footage, and will lead to better living.

House A is not the best house to live in but you know that being close to the center means ample job opportunities. Conversely, jobs close to House B are not great but will make for a good living. You do not have the cash to afford the house outright and will need to finance it.

Nepal is the home buyer in this case and the houses are its two options. Option A, similar to House A, is to take foreign financing–which it needs–to build hydropower projects and allocate it primarily for productive usage. Option B is to build hydropower projects to fuel consumption–economic activities that end at the point of consumption. Their first order effects would be job creation for whomever is providing the good or service to be consumed.

Using electricity for productive assets means building factories that run off hydropower. It means using innovative technologies to fuel agriculture and transport. It also means to explore and expand the frontier of technology by allocating clean energy for computing, powering the blockchain, powering data centers etc. Using electricity for consumption means to light up shopping malls, heaters, induction ovens, tvs, computers, luxury electric vehicles etc.

It is a delicate microeconomic process that governments, corporations and definitely individuals are powerless against. To suggest a more austere life of working with lower quality of life with the promise of future returns is an ivory tower esque task. But it is my belief, and hence a key part of Taruka’s mission, to do exactly that. I used a lot of words and you, the reader’s time, to delve into this esoteric argument of how Nepal’s electricity should be used. That’s for a reason. And it ties back to Taruka’s Raison D'Être.

Fundamentally, we want to empower Nepalis. We believe proper usage of hydropower is the way to do so. We plan to do the actual empowering by building electric tools, vehicles, mobility equipment and utility devices. And that’s the hard part.

The W’s

What the hell do you mean when you say you want to empower Nepalis? Who are you empowering? When is it going to happen? And where? Why is that your mission? Who do you think you are to be attempting such a thing? Why do you think you’ll be successful? And, how exactly?

Because of how fundamental the term empower is for our mission, I’ll begin this section with the cliche of deferring to Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster defines empower as, “to give power to (someone)”. Taruka’s mission is to give power, in a broad sense, to Nepalis. We aim to empower them by allowing for cheap and efficient mobility across the rugged terrain. We aim to empower them by reducing the manual labor required to increase agribusiness profits.

Though we say, our mission is to empower Nepalis. We begin with a small subset. Our early products will be geared towards businesses that have cash flows large enough to afford and sustain Taruka’s products. Our products will be priced at around four to five thousand USD. This is a premium for many farmers to afford. Thus, we need to target our first product towards businesses who will benefit a lot but can also afford it.

I’ll briefly explain why we phrase the first part of our mission as, “to empower Nepalis to use the nation’s hydropower resources”. Cheap, clean electricity produced by the many flowing rivers is Nepal’s oil. One may think that empowerment begins on the production side, not on the demand side. The issue with Nepali hydro is that production is low, not that people don’t have ways to use it. To counter this line of thinking, I appeal to the above argument about using electricity for productive usage. Taruka is building tools that maximize the utility of electricity instead of, say, building heaters or induction ovens.

Taruka is beginning its operations in 2022. Though it’ll take a few years for the company to scale and have enough technology and engineering know-how in the back pocket, I believe we can generate sales and have a top line number within a few iterations of our main product. Taruka is based in the Kathmandu Valley. We’re currently working out of a small workshop leased to me by my father free of charge. At our workshop, we’ll be doing research into electric vehicles. We’ll be doing exciting engineering to design in house parts. We’ll be creating prototypes, iterating on our designs and making each part meet our high quality standards. Using the tools we create, we’ll plow and till fields, plant trees and haul goods for farmers and citizens alike. We’ll collect data on the effectiveness of our products and compare that with what’s available in the market–to ascertain the efficiency of our products.

As for who we are and why we’re attempting such a project, our team has two of the best engineers in Kathmandu, both graduated from top engineering universities. Our product development team will be led by me, Gaurav Dahal, fearless and optimistic. I’ve left my comfortable life in the US, postponed my dreams of writing a science fiction novel, all to build an enterprise that will bring prosperity to this poor Himalayan nation. There’ll be very little in terms of drive and determination to stop me. Though our team is small, we have the gumption to take on any challenge the Universe throws at us. At Taruka, we say, “we only take NOs from the Universe. Nothing and No one else.”

Why will we be successful?

To answer this question requires an esoteric delving into some macroeconomics.

Let’s start with some facts. In 2019, Nepal had a trade deficit of around nine billion dollars. The Himalayan Times reported that 1.43 million hectares of land is left uncultivated out of a total of 3.9 million hectares, roughly one third.

Every year, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development publishes a statistical factbook calledStatistical Information on Nepalese Agriculture. Similarly, every year the Department of Customs releases their report on Foreign Trade detailing every item imported to Nepal and exported from Nepal. The statements and arguments below appeal to data provided by these two government bodies.

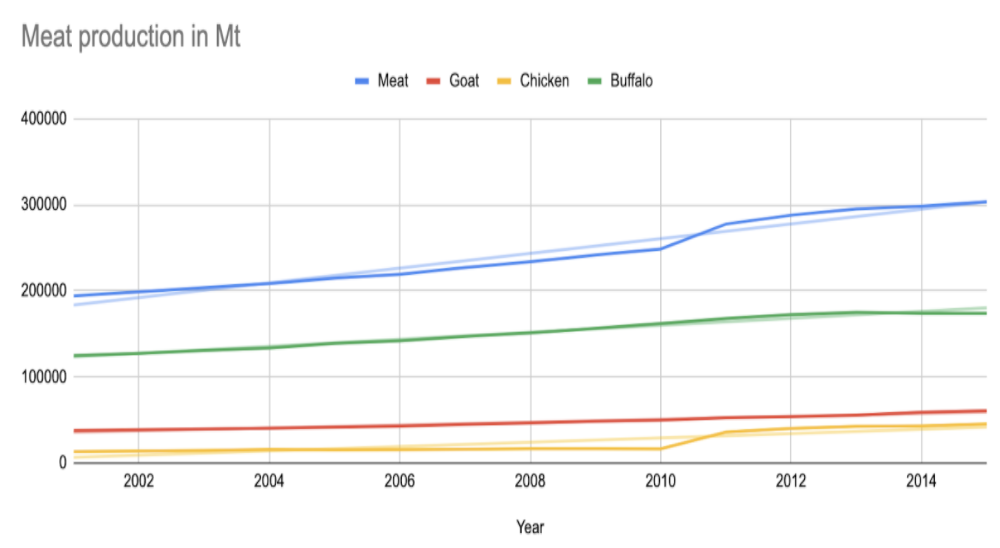

Some trends that we know to be true are that investment in agribusiness in Nepal is increasing. Poultry production in Nepal has nearly tripled from 13,000 metric tons in 2002 to 45,000 Mt in 2015. The chart below shows the meat production data provided by the Ministry of Agriculture from 2002 to 2015. We hear the term “Krishi Kranti” in Nepal, a salve many prescribe to ward off the disease of young men and women leaving the country as exported labor.

Another general trend we’re seeing world wide is that electric vehicles are increasing, battery technology is improving and getting cheaper and that the world is slowly turning more electric. On a similar vein, production of hydroelectricity in Nepal is increasing.

Now that we have the facts down, it’s time to arrange the puzzle pieces and connect the dots. Nepal has a trade deficit. Nepal has a lot of arable land uncultivated. Nepalis are leaving the country due to a lack of domestic jobs.

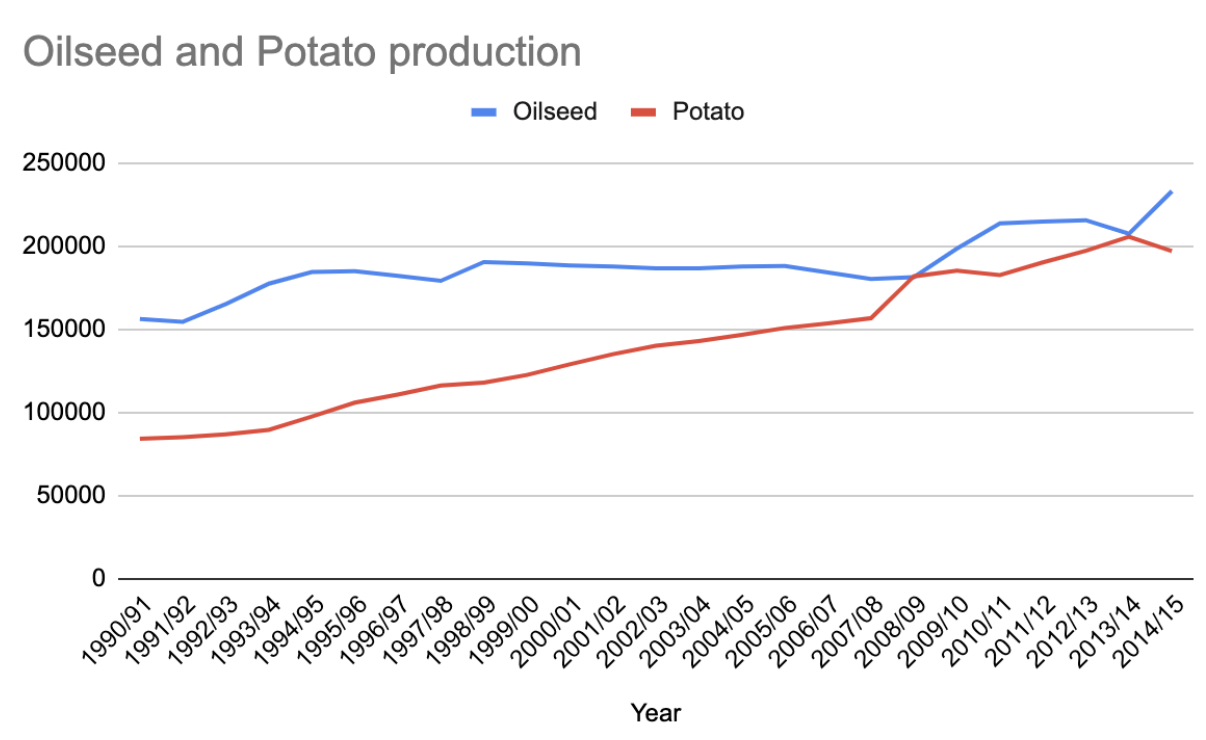

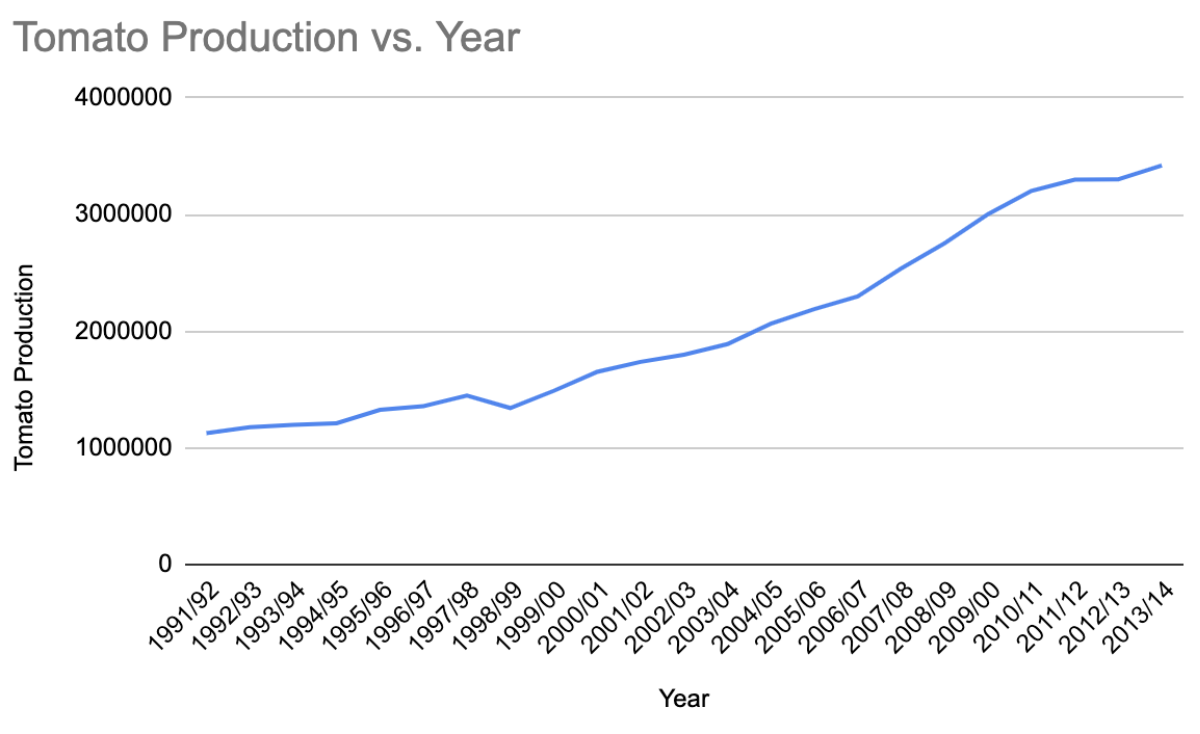

This is where Taruka comes in. Taruka, in chasing to complete our mission, will employ hundreds of thousands, not as engineers or factory workers, rather by creating tools people can use, namely for agriculture. The genius in this strategy stems from the fact that Nepal imports agricultural goods that can be grown in Nepal. Though the trade deficit is not all agricultural goods, more than a billion dollars are spent yearly in importing food and foodstuffs alone. In 2019, Nepal imported $40 million worth of potatoes, $75.6 million worth of apples and pears, $242 million worth of rice. These are all crops that can be grown in Nepal–just not economically.

So what if we put two and two together? Nepal has a lot of land uncultivated? Okay, we’ll build tools that make cultivating land easier and efficient. Nepal has cheap and clean electricity? Okay, our tools will run off domestically generated hydropower. Nepalis are leaving the country due to a lack of jobs? Well, who wants to plow fields by hand and carry dokos of goods, I don’t. We’ll create tools that replace antiquated farming methods so that young people feel proud of the farming they do. And, the cherry on top is that as the years go by, our machines will get cheaper and better without us doing anything. How? Because the global battery market and companies like Tesla and CATL are making it so. We ride the tidal wave of technological progress brought on by technology giants such as these.

The best of all, as an environmentalist and someone deeply anxious about the existential threat that is climate change, our company will not only have a clean footprint on the planet, but it will actively fight the foe that is carbon emitting agriculture and mobility. We will not only promote the use of clean energy in places where dirty energy is used, but we will force the clean energy industry in Nepal to grow and to keep up with the rising demand for energy our tools will bring.

P.S. Nepal’s biggest import is refined petroleum, worth more than 1.3 billion dollars. Imagine how much money we can keep in the country if we manage to reduce 5-10% of petroleum imports.

I hope in this blog post I have given not only a reason for why Taruka could exist but also given you enough of an understanding of Nepal’s complex economy to paint a clear picture for why Taruka should exist. We believe Taruka is paramount to Nepal’s development. I do not see a world where farmers have to hammer away on compact clay with their kodalos and move goods on their dokos. I envision a Nepal where even the poorest farmer owns an electric mobility device to aid them in navigating the rugged mountain terrain. I envision Taruka being the company that takes Nepal from a struggling economy with a massive trade deficit to an efficient economy– a powerhouse in agriculture with income generated by exporting specialty Himalayan crops. We cannot change what we have, we can only embrace it and make it better. Taruka is the company that will empower Nepalis to embrace Nepal for what it is and take it where it can go.

Sincerely,

Gaurav Dahal

Founder and CEO,

Taruka Tech.

Appendix

All data, facts and ideas not mine are cited below.

https://customs.gov.np/storage/files/1/FTS/Annual_FTS_pdf.pdf

https://oec.world/en/profile/country/npl

https://www.moald.gov.np/publication/Agriculture%20Statistics

https://kathmandupost.com/opinion/2018/06/12/young-country-fallow-lands

https://kathmandupost.com/miscellaneous/2014/06/30/govt-to-declare-decade-of-agriculture-revolution

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=NP

Source: https://www.moald.gov.np/publication/Agriculture%20Statistics

Source: https://www.moald.gov.np/publication/Agriculture%20Statistics

Source: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/breaking-the-barriers/

http://www.doanepal.gov.np/downloadfile/tomato%20book_1614144109.pdf

According to Demand and Supply Situation of Tomato in Nepal, it is noted that, “Tomato is labor intensive crop, wage alone constituting half of the total 8 Demand and Supply Situation of Tomato in Nepal cost of production.”